Descended from a great-great grandfather who was enslaved in North Carolina, Newark resident Onnie Strother who maintains an Art studio in the Riker Hill Art Park in Livingston, has made a life’s work inspiring and teaching young people about Art, and educating people of all ages about the Black Experience in America.

He grew up in Newark attending Saturday Art classes for kids at Arts High at age 9, and later attended Barringer High School where through mentor John Morello, he discovered Black artists and got, as he says: “serious.” After high school, he attended New York’s School of Visual Arts on scholarship, and because this notable professional Art school had just become certified as a college was the first student to receive a bachelor’s degree. Spending a semester at Essex County College passionately focusing only on Black Studies was a life changing experience.

Subsequently at the suggestion of his next mentor in Newark, Ruth Assorson, he registered at Rutgers and got certified as a public-school Art teacher which led to a job at Columbia High School which serves the South Orange/Maplewood district. While there, he had a storied career and served for 24 years, in the process instituting numerous cutting-edge programs and courses.

In 2004, at the invitation of Eleta Caldwell, he became the Art Department Chair at Arts High in Newark until his retirement in 2008. Since that retirement from public school education, Strother has focused on curating exhibits of other artists at many venues in the region, teaching printmaking at the WAE Center, a facility for the developmentally disabled in Livingston, and creating his own Art.

Strother seems to find his momentum when working on efforts that are part of a series, one of which called 100 Selfies is represented here. Troy is a 16x20 oil painting on canvas. Fascinated by watching teenage girls use their cell phones in that way that previous generations of women used makeup compacts to look at themselves, he had people submit selfies that they had taken using phones or iPads. It was important to him that the photos represent the subjects the way they saw themselves, and it was those self-portraits that Strother then recreated as oil paintings.

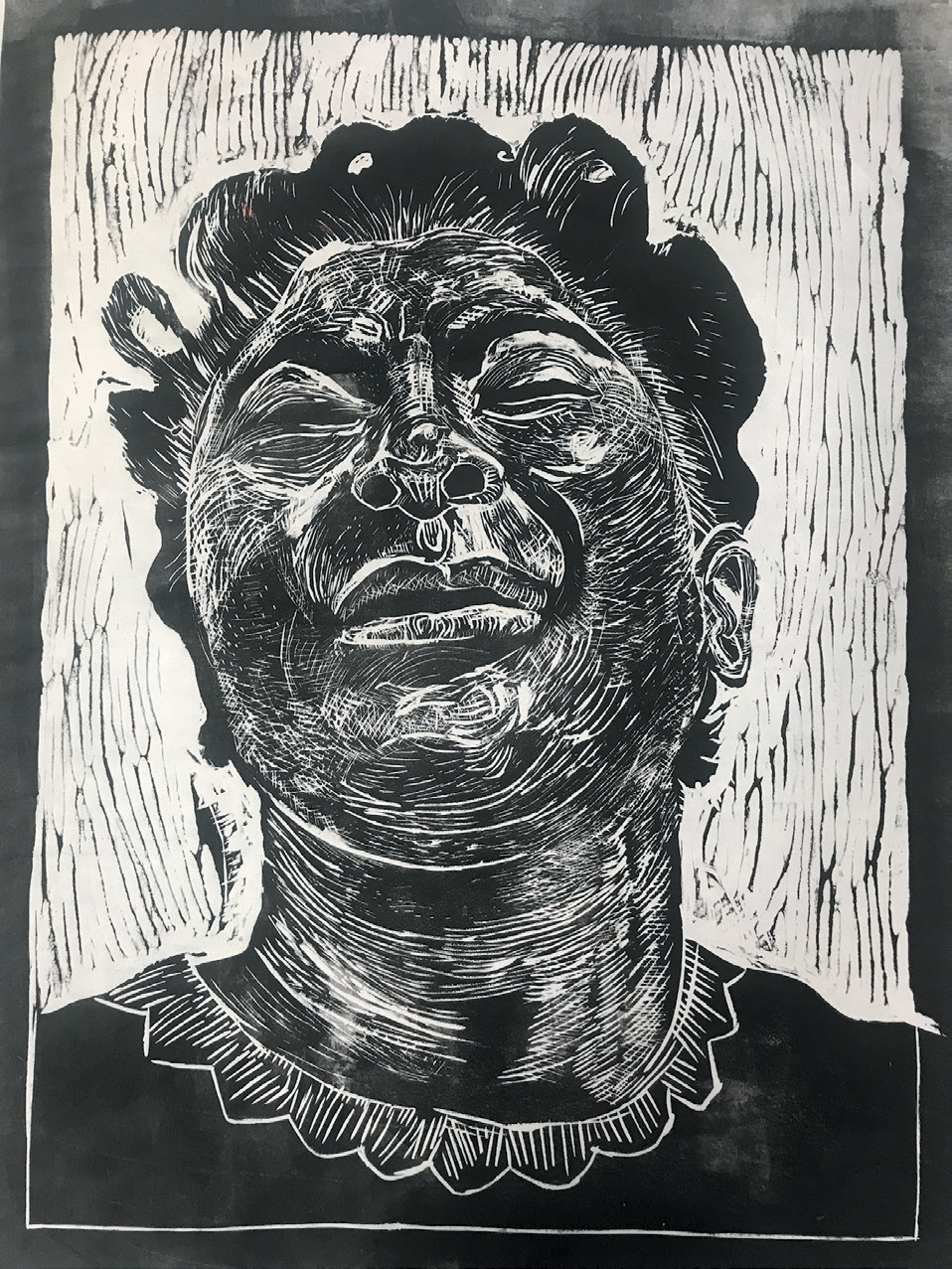

“When people think about divas, they don’t think about Gospel,” Strother says. And that was what inspired him to approach the subject. In a series that celebrated Gospel divas such as Big Mama Thornton and Sister Rosetta Tharpe, here we share a 16x20 linoleum block print on rice paper, titled Elijah Rock, which depicts gospel great Mahalia Jackson performing one of her more well-known songs. Her connection to God and that feeling is palpable in this work in which Strother truly captures her spirit.

In Mike’s Scottsboro Boys, a 24x36 Monoprint which includes transfers, drawing, and painting Strother reminds us about this sad time in our history wherein 9 African American young men aged 13 to 20 were falsely accused of raping two white women. The landmark set of legal cases from this incident dealt with racism and the right to a fair trial. The cases included a lynch mob before the suspects had been indicted, all white juries, rushed trials, and disruptive mobs. It is commonly cited as an example of a legal injustice in the US legal system. In the 1930s, there were many Hollywood films about legal injustices, all featuring white heroes such as the 1932 film, I Am a Fugitive from A Chain Gang. In this work, Strother draws a contrast between the fictional film with a true story; one of the boys did escape. There were nine boys, and as such, Strother had had a series of 9 prints made of the original mono print.

Emmett Till was a 14-year-old African American boy who was abducted, tortured, and then murdered in 1955 in Mississippi after being accused of offending a white woman in her family’s grocery store. His killers were acquitted and Till became an icon in the long history of violent persecution of black Americans in the US. Strother’s work: Big Boy Emmett Till a 20x24 collage with painting and drawing draws our attention to this heart aching moment in American history. Even though Till’s body was brutally mutilated his mother insisted on an open casket at his funeral so that everyone could bear witness to the injustice, and likewise Strother demands that we also bear witness and memorialize this life.

This recipient of grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation has spent his life not only teaching and inspiring young people to make Art, but teaching all of us through his personal Art, and calling attention to the sorrows as well as the profound joys found in the Black History in America.